"Your God is My Devil"

A lesser-known John Wesley quote for such times.

John Wesley isn’t the Protestant reformer most well-known for his insults. That honor goes to Martin Luther, whose repertoire for reading his enemies for filth was so deep that there’s a whole Web 1.0 site dedicated to resurfacing them.

And yet, Wesley reportedly delivered the barn-burner line “Your God is my Devil!” in a debate with a contemporary Calvinist preacher.1

That line resonates deeply in recent days.

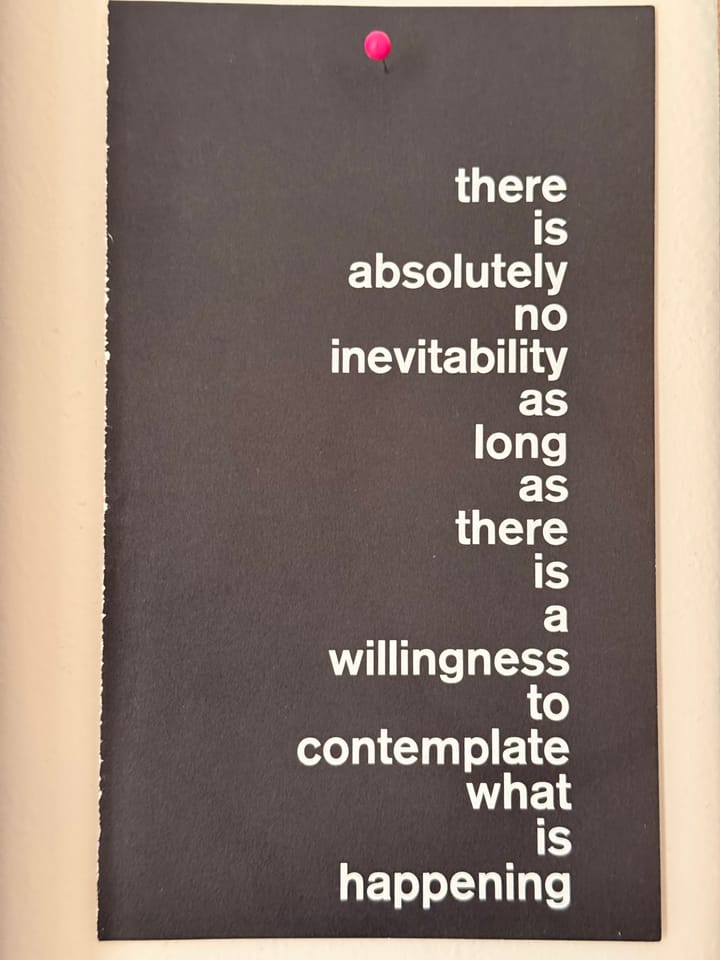

In my book I wrote this:

“The steadfast evangelical commitment to never changing is not a virtue but a vice, and one that is costing them and us dearly. It is not a good thing that Harry Emerson Fosdick’s description of the fundamentalists of his time in the 1920s applies just as well to the fundamentalists of the 2020s. By routinely refusing to revisit what they have deemed “orthodoxy,” they have reduced themselves to circling the same issues again and again, methodically rejecting new information and reinforcing their worldview. Their commitment to remaining in the 1920s alienates and isolates them. It leads to a faith that stifles growth instead of encouraging it.”

Within American Christianity,2 the internecine battles of the “fundamentalist-modernist controversy” during the late 19th/early 20th centuries set the stage for what would become our never-ending culture war. While the original arguments were doctrinal—about whether the Christian scripture was “without error”—the staunch ideology of the fundamentalists encouraged a reactionary response that outright rejected new information (but, interestingly, never questioned new communications technologies) that conflicted with their worldview.

Following the Pyrrhic victory of the Scopes Monkey Trial where fundamentalists won in the court of law but lost in the court of public opinion, the fundamentalists began building or expanding their own alternative institutions: schools, presses, radio stations, stores, and denominations.

Over time, their power, wealth, and influence grew. Through the neo-evangelical period of the 1940s where key figures like Billy Graham ingratiated themselves to business interests and the National Association of Evangelicals was founded (by only white evangelical groups) apart from what is now the National Council of Churches, a nominal evangelical public formed in opposition to the “mainline” denominations. The Civil Rights era drove a further wedge, and by the 1970s, the modern Religious Right was primed to take shape.

This is a broad-strokes retelling—there’s a reason entire shelves of books have been written about this topic. But my point remains: at least two very different visions of Christianity have been vying for power in the United States for well over a century.

A very particular vision of Christianity is being enshrined in American politics, one that most white evangelicals—80% or more voting for Trump across three elections is enough to say this without reservation—are comfortable with, as are many conservative Catholics, Pentecostals, and charismatics. This nationalist version of Christianity is the one benefitting from the executive order on “anti-Christian bias,” even as mainline Protestant and Catholic charities are targeted by the likes of the vice president, Elon Musk, and disgraced General Michael Flynn.

These actions make blatant what many people (like myself) who have participated in both conservative evangelical and progressive mainline denominations know innately: Christian nationalists do not see other Christians as valid, and instead see & treat their fellow siblings in Christ as enemy combatants. A common courtesy of shared faith is not extended. Fundamentalists and nationalists do not believe they worship the same god, and they are comfortable enforcing their view of God on people through governance. Their actions belie their motivations: that they want dominance and compliance more than they wish for any other aspect of the story of Jesus and the long and diverse history of Christianity.

I wrote last month about the ‘clash of Christianities,’ and I must say I can’t muster any enthusiasm for theological nitpicking of any kind at the moment. I’m not interested in whether “Christian nationalist” is the right term to use, or to stipulate between evangelicals, charismatics, Pentecostals, and hard-right Catholics, or the gradients of difference between various progressive strands of Christianity. What is self-evident is that there is Trump-approved Christianity, and there is everything else, and these forces are in opposition.

Their God is my devil. And they feel the same about me.

They likely read “woe unto them who call good evil, and evil good” and think of someone like me, an exvangelical apostate leading others astray, while I think of the Christians who cheer the reduction of USAID (an agency they likely never thought much of at all before Musk targeted it) despite the massive deleterious effects this will have on global public health.

It’s just the Spider-Man meme, stretched over an entire century—but one of these Spider-men has control over the Presidency and no interest in the equitable pursuit of freedom of religion.

There are a handful of things that keep circling in my mind: the song “Wolves At The Door” from David Bazan’s album Strange Negotiations, Melissa Florer-Bixler’s book How to Have An Enemy, and Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works. But those thoughts will have to wait for another time, when some positive chemicals can counteract the negative ones holding sway this evening.

The sourcing is muddied, with some pointing to an attribution in a subsequent work by William Barclay. However, there’s a whole Wesley sermon about how the God of Calvinism—and specifically the doctrine of predestination—makes God “worse than the devil.” ↩

I would often specify White American Christianity, but I honestly do not know enough about the prevalence of fundamentalism within historically Black Protestant traditions or other traditions. There are books on the topic, but I have not had the honor of reading them yet. ↩

Comments ()