Heart on a swivel

Evangelicalism and the questioned sense of belonging

I don’t know about you, reader, but in my experience, evangelicalism breeds a certain type of distrust that I haven’t experienced elsewhere. It is quiet, subtle, and gradual; I’m certain it exists in other faith communities, too, but we’re going to Stay in Our Lane as much as possible here at PEP. Here’s a couple examples: one drawing from my life, and another presented as a story.

At Christian college, anyone could be a narc.

Christian college is a prolonged exercise in gauging levels of trust in nearly every interaction. It presents itself as a place where faith is encouraged and explored, but in many colleges, that exploration has clear boundaries and confines. This isn’t always hidden from view; Christian colleges typically require both statements of faith and morality contracts for their students.

When I applied to Indiana Wesleyan, I was young and idealistic. I had felt a call to ministry in high school, and was intent to set out on my journey to the pulpit. The summer before freshman year, I was certain that college would be different, because Christians are different - and we would all be Christians on campus, and be kind to one another and grow in knowledge of the Lord, and everything would just be swell.

I was wrong. My Christian college experience was just as cliquey and human and status-driven as high school was, but with a gloss of Christianese over it all. I had thought that the college experience would be a freeing place to explore the depth of an ancient faith. Instead, there were rules about which movies you couldn’t watch (anything rated R, except for things like The Passion of the Christ and The Matrix, because violence = salvation and spiritual warfare), how many times you attended chapel, when and how the opposite sex could visit your room, and other things crucial to our “formation.” And anyone - anyone! - could tell on you. Every person could be a narc, and let your RA or your dorm leader or some other authority know that you’d smoked a cigarette or watched Super Troopers. It takes normal behavior and treats it as deviancy.

This kind of environment breeds paranoia. Trust is not something you give out easily.

Small group unease

It’s a common enough event: a book study for a church small group. It happens all over the country and all over the world. You’re sharing your thoughts on Francis Chan’s Crazy Love or John Piper’s latest love letter to John Calvin. And then you let slip something like “attributed to Paul,” imply that something may not be literal, or maybe even disagree with the text entirely.

Something enters the air that wasn’t there before. It’s an unease you’ve felt before, when you’ve dared to share something personal and it is met with shock and confusion. You make a ham-fisted segue, and try to move on. But later on you’ll remember how it felt, how even as the conversation went on you were still preoccupied with how people responded to you and your words, how you felt as if you were weighed and found wanting.

You may even talk it over with your spouse afterward. If you trust them.

Always on a swivel

Let’s come back to the question of trust, and how it relates to belonging. I started thinking about this after reading Mason Mennenga’s thread on Twitter:

I had a conversation with a seminary student yesterday whose main religious tradition had been evangelicalism prior to attending seminary. He said to me that while he’s appreciative of the liberal mainline tradition, he mourns that he simply cannot find a home in it. 1/5

— Mason Mennenga (@masonmennenga) 7:15 PM ∙ Feb 5, 2020

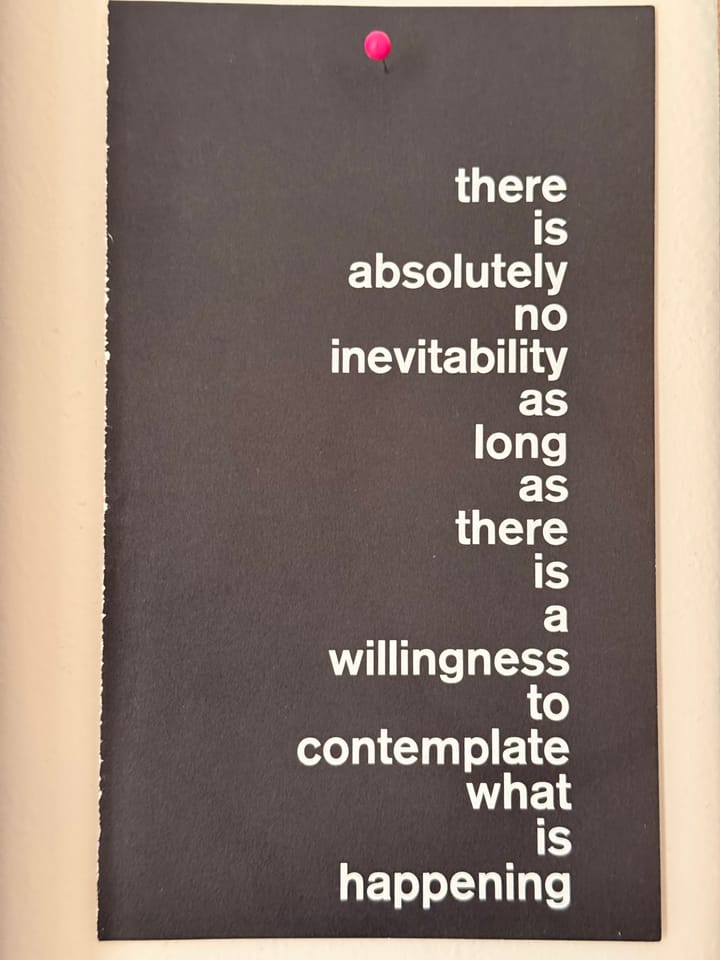

The whole thread is worth a read: it acknowledges that many people who leave evangelicalism but remain Christian become as Mason says “ecclesially homeless.” I understand that sentiment, and still wonder: how much does evangelicalism itself cause us to constantly measure ourselves up against the group? We are taught to “test the spirits” and we end up testing ourselves; we are told to “pray without ceasing,” and we compulsively check every whim and thought.

There are spoken and unspoken orthodoxies in white evangelicalism, knitted together alongside the theology and traditions. We test our relationships with them constantly. And when our convictions, or the stirring of our hearts, or our need to survive send us beyond evangelicalism, we carry those behaviors with us.

We do not know if we can belong, if we cannot trust and be trusted. Our hearts are on a swivel, waiting and anxious.

I don’t have a cozy conclusion to this essay. I want to belong, and I want to trust and be trusted. But I don’t want that belonging to be dependent on adhering to certain set of beliefs. Beliefs change, because people change. Expectations of community change, too. I do know this, though: now that I am aware of this behavior, I no longer want to repeat it.

Thanks for reading this first issue of the paid version of The Post-Evangelical Post. Please let me know your thoughts; in these early days, the format may change as it reveals itself. Some editions may feature essays like this, while others will include news stories and other links (expect that on Friday’s edition this week).

I also want to test out the comment and thread functions of Substack. Please reply to this post: Where have you found community beyond evangelicalism? Further: what did you want out of that community?

Comments ()